Related Articles

Relevant Topics

-

Abood v. Detroit Board of Education

-

AFL-CIO

-

Alabama

-

Arkansas

-

Bureau of Labor Statistics

-

California

-

Colorado

-

Congressional Research Service

-

Connecticut

-

Dell Technologies

-

Economic Policy Institute

-

First Amendment to the United States Constitution

-

Harris v. Quinn

-

Honda

-

Idaho

-

Illinois

-

Indiana

-

Indiana Supreme Court

-

International Union of Operating Engineers

-

Iowa

-

Kansas

-

Knox v. SEIU

-

labor union

-

Las Vegas

-

law

-

Massachusetts

-

Medicaid

-

Michigan

-

Minnesota

-

Mississippi

-

Missouri

-

National Labor Relations Act of 1935

-

National Labor Relations Board

-

Nebraska

-

Nevada

-

New Mexico

-

occupation

-

Ohio

-

Oklahoma

-

Oklahoma Supreme Court

-

Oregon

-

PepsiCo

-

preference

-

Samuel Alito

-

Supreme Court of the United States

-

Taft–Hartley Act

-

Tennessee

-

Texas

-

The Heritage Foundation

-

Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

-

Thomas Jefferson

-

United States Congress

-

United States Constitution

-

United States Department of Commerce

-

United States of America

-

Verizon

-

Vermont

-

Washington

-

William B. Gould IV

Click here to download a PDF of this policy brief which includes sources and citations.

Key Findings

- Studies show that states with right-to-work laws attract more new business than states without such laws and also typically have a better business climate than non-right-to-work states.

- Once cost of living is accounted for, workers in right-to-work states enjoy higher real, spendable income than workers in non-right-to-work states.

- Federal law does not require unions to represent non-members; unions are only required to represent every worker if they choose to invoke federal law giving them “exclusive bargaining representation.”

- Union membership has been declining nationally for three decades. Public support for labor unions appears to be fading.

- Right-to-work laws do not ban unions or prevent them from serving the interests of their members. Rather, right-to-work laws require unions to give workers a choice about financially supporting those efforts.

- Recent decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court in Harris v. Quinn and Knox v. SEIU indicate the Court may be willing to overturn a previous decision (Abood) that requires government employees to pay union dues or agency fees, even if they do not want union representation. Such a ruling would likely lead to the same rights for private sector workers.

Introduction

The issue of right-to-work, the right of a person to hold a job without having to pay dues to a union, is steadily taking center stage across the country as states strive to improve their ability to create jobs, promote economic development and attract new businesses. Two states, Indiana and Michigan, recently enacted right-to-work laws, also called “workplace freedom” or “workplace choice,” with more states introducing legislation and debating the issue every year. Currently 24 states have right-to-work laws.

In states with right-to-work laws, workers can choose not to join a union and not pay dues. States without right-to-work laws do not allow workers that choice, instead requiring employees to pay union dues or “agency fees” as a condition of employment.

A right-to-work law does not prohibit employees from joining a labor union, nor does it prohibit them from paying union dues voluntarily. Labor unions still operate in right-to-work states, but the law protects each person’s freedom of association by prohibiting the payment of union dues from being a required condition of employment. The principle right-to-work laws seek to protect is that no one should be forced to choose between paying money to a cause he or she might oppose and making a living.

Opponents says right-to-work laws give non-union members a “free ride” in the workplace, enabling them to benefit from union representation and union-secured benefits without sharing in the cost of negotiating those benefits. They argue the “free riders” ultimately result in more and more workers leaving the union, undermining the stability and financing of the union itself. For that reason opponents often describe efforts to pass right-to-work laws as “union-busting.”

This study provides background on the history of right-to-work legislation and explores the impact right-to-work laws have had on states.

Background

Congress enacted the National Labor Relations Act (NRLA), known as The Wagner Act, in 1935 to regulate and protect the right of workers to unionize and collectively bargain for wages and benefits. The law sanctioned collective bargaining agreements negotiated between employers and labor unions that created “closed shops” and “union shops.” A closed shop requires employers to hire only current union members. A union shop forces employers to require that anyone hired by the company join the approved union and pay union dues as a condition of employment. Known as a union security agreement, the provisions removed any choice from the worker and guaranteed a steady income for the union.

The NRLA was considered by many as giving labor unions too much power over labor policies. For example, the NRLA established a list of unfair labor practices by employers, but not on the part of labor unions.

In 1947, the Taft-Hartley Act sought to remedy the perceived imbalance of the NLRA favoring of labor unions. The Act amended the NLRA to include a list of unfair labor practices by labor unions. It also prohibited closed shops and restricted union shops in favor of “agency shops,” wherein a worker does not have to become a full member of the union, but must pay an “agency fee.” An agency fee is the portion of union dues used to represent workers in collective bargaining and provide services to all represented workers. The portion of dues used by a union for political activities or for organizing employees of other companies is excluded from the agency fee.

The Taft-Hartley Act also gave states the authority to enact “right-to-work” laws prohibiting mandatory agency shops and agency fees. In these states, a worker cannot be required to join a union in order to gain or keep employment, nor can they be required to pay any portion of union dues, such as agency fees. Instead workers in these states have the right to reject union representation and the corresponding union dues or agency fees. Within a year of the Taft-Hartley Act, 12 states passed right-to-work laws.

Today, 24 states are right-to-work states. In 2012, Michigan and Indiana became the most recent states to pass right-to-work laws. That same year, 17 other states debated right-to-work legislation. The year prior, in 2011, 16 states considered right-to-work bills. In 2013 the number of states introducing right-to-work legislation jumped to 21, along with legislation introduced in the U.S. Congress to create a national right-to-work law. Missouri and Ohio are widely considered the next battleground states for right-to-work efforts.

Legal challenges have been mounted against Indiana’s new right-to-work law; two state judges have ruled the law unconstitutional and the case will be heard by the Indiana Supreme Court this fall.

The Research on Right to Work

Studies show that states with right-to-work laws attract more new business than states without such laws. Right-to-work states typically have a better business climate than non-right-to-work states, and employers value the labor-management predictability inherent in stable right-to-work states. Employers in right-to-work states are not encumbered by disputes or the threat of work stoppages from unions. Right-to-work laws ensure companies and workers will enjoy labor peace over the long term.

In fact, right-to-work status is considered a major factor in a business’s decision about where to locate. One professional site consultant, whose clients include AT&T, Chevron, Dell, Honda, PepsiCo and Verizon Wireless, says, “Manufacturing companies look for reasons to scratch off states when considering where to build major facilities—and no right-to-work law is at the top of the list. I can’t underscore how critical right-to-work status is.”

Another professional site consultant agrees, saying that 50% of manufacturers automatically screen out any non-right-to-work state.

Nationally, the top three states for new manufacturing jobs are right-to-work states (Michigan, Texas and Indiana), and four of the five top states for total manufacturing jobs are right-to-work states (Indiana, Arkansas, Michigan and Alabama). A study of bordering counties located in right-to-work and non-right-to-work states found right-to-work counties have one-third more manufacturing jobs than their non-right-to-work neighbor across the state line.

It is not coincidence that foreign automobile brands have located their U.S. plants primarily in right-to-work states like Alabama, Tennessee, Mississippi and Indiana. According to the National Institute of Labor Relations Research, between 2002 and 2012, before Indiana and Michigan passed right-to-work laws, the 22 states with right-to-work laws saw their share of nationwide automotive manufacturing output increase from 36% to 52%. Real manufacturing GDP in those 22 right-to-work states grew by 87% during that decade, but fell by 2% in non-right-to-work states.

The Congressional Research Service found that in the past decade, “aggregate employment in RTW states has increased modestly while employment in union security states has declined.” Other studies echo these findings. Both employment growth and manufacturing employment growth have consistently been higher in right-to-work states compared to non-right-to-work states over the past two decades.

The average unemployment rate of right-to-work states is typically around 10% lower than in non-right-to-work states. In June 2014, the national unemployment rate was 6.2%, while the average in right-to-work states was 5.5%, a rate difference of more than 11%.

Another study found that “incomes rise following the passage of right-to-work laws, even after adjusting for substantial population growth that those laws also induce. Right-to-work states tend to be vibrant and growing; non-right-to-work states tend to be stagnant and aging…the overall effect of a right-to-work law is to increase economic growth rates by 11.5%”. Yet another study found right-to-work states outperformed non-right-to-work states in employment growth, population growth, in-migration and personal income growth.

The experience of Michigan bears this out. The state’s unemployment rate dropped from 10.4% in 2011 to 8.7% in 2013 after the right-to-work law went into effect. The 2014 budget proposed by Michigan’s governor predicts the state’s growing auto and automotive parts production will reduce unemployment to 8.3% in 2014, 7.5% in 2015 and 6.7% by 2016.

Michigan also enjoyed the ninth highest increase in per-capita income in the nation, from $38,291 in 2012 (before right-to-work became law) to $39,215 in 2013, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Similarly, research suggests that foreign direct investment and manufacturing employment in Oklahoma and Idaho increased significantly after these states passed right-to-work laws.

Does Right-to-Work Mean Work-For-Less?

Opponents of right-to-work laws disparagingly refer to them as “right-to-work-for-less” laws. They claim workers in right-to-work states earn lower wages than employees in non-right-to-work states.

Right-to-work states generally have a significantly lower cost of living, meaning a relatively lower wage will support the same or better standard of living as a family living in a costlier non-right-to-work state. So the lower than average wages in non-right-to-work states are offset by the lower cost of living in those states.

In the first quarter of 2014, 20 of the 25 states with the lowest cost of living were right-to-work states. The remaining four right-to-work states ranked between 29th and 35th. No right-to-work states fell in the top 15 states with the highest cost of living.

Once cost of living is accounted for, workers in right-to-work states actually enjoy higher real, spendable income than workers in non-right-to-work states. As one researcher put it, “RTW states have average wages that are significantly higher than non-RTW states.”

The Arguments For and Against Right-to-Work

The arguments supporting right-to-work laws are simple—workers should have the freedom to decide whether they want to support a union financially. If workers find sufficient value in the representation and services provided by a union, they will voluntarily pay union dues to ensure the continuation of those services. If they do not believe they are receiving sufficient value, or if they oppose the political activities of the union, they should not be forced to support the union. This core principle is summed up in Thomas Jefferson’s statement about freedom of association:

“To compel a man to furnish contributions of money for the propagation of opinions which he disbelieves and abhors is sinful and tyrannical.”

The arguments against right-to-work claim such laws are designed to cripple unions by allowing “free riders” to take advantage of the representation and services provided by a union without sharing in the cost. Opponents say federal law requires unions to represent all workers at a company, whether or not they pay union dues, leaving unions in an impossible situation:

“Under a right-to-work law, people could withdraw from the union and wouldn’t have to pay anything. But we are still obligated by federal law to represent them like we would represent a member.”

But this view is not accurate.

The NRLA does not obligate unions to represent non-members. Under federal law, unions are allowed to bargain solely for their own dues-paying members under a “members-only” contract. The benefits secured under these contracts apply only to dues-paying members. As noted by former chairman of the National Labor Relations Board William Gould, “the law now permits ‘members-only’ bargaining for employees.”

Unions are only required to represent every worker, even non-dues paying members, if they choose to invoke federal law allowing them the privilege of “exclusive bargaining representation.” This monopoly bargaining option allows unions to represent and negotiate on behalf off all employees in a company, regardless of whether every employee wants that representation. If unions opt to insist on exclusive representation, the law then requires them to negotiate fairly for all workers. That is, the union cannot negotiate a lower wage that discriminates against non-members.

If a union decides against exclusive monopoly bargaining, choosing instead to negotiate only on behalf of its own members, it is not required to represent non-members. In that case only the members with a signed contract are required to pay dues and the union negotiates only for those members. In practice unions almost always seek exclusive representation status, since it gives them a monopoly position in the workplace.

Why would a union choose to exclusive representation over members-only contracts? A Heritage Foundation study explains:

“They [unions] prefer exclusive representative status because it enables them to get a better contract for their supporters. Consider seniority systems: They ensure that everyone gets raises and promotions at the same rate, irrespective of individual performance. If a union negotiated a members-only contract with a seniority system, high-performing workers would refuse to join. Those workers would negotiate a separate contract with performance pay. The best workers would get ahead faster, leaving less money and fewer positions available for those on the seniority scale. The union wants everyone in the seniority system—especially those it holds back.”

So unions make the decision to negotiate as an exclusive representative in order to reap the benefits it provides, then use that choice as the justification for forcing employees to pay for representation they may not want. In non-right-to-work states, workers who refuse to join the union but must still pay union dues, or agency fees, are forced to pay for representation that results in labor contracts that may be harmful to their economic interests. For example, a high performing worker is required to pay for a contract that rewards workers who are lower performers, but who have greater seniority, and who thus receive higher wages and better benefits than they could otherwise earn.

Some unions have made the shocking claim that forcing union workers to work alongside non-union workers is equivalent to slavery. The International Union of Operating Engineers Local 150 filed a lawsuit in 2012 to overturn Indiana’s right-to-work law on the grounds the law is a violation of the Thirteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, because union members are forced to work with those who are not members of the union. Passed in 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment outlaws “slavery” and “involuntary servitude” in the United States. This union says it has been forced to work for free (the lawsuit calls it “involuntary servitude”) for non-union workers because those workers do not pay union dues.

Is Right-to-Work Union Busting?

Right-to-work laws do not prohibit unions. Rather, unions must prove their value to workers and establish a voluntary relationship with them. A voluntary relationship forces union executives to be more responsive and accountable to workers, and to do a better job.

In general, union membership is lower in right-to-work states. But right-to-work laws do not necessarily translate into lower union membership. For example, one of the most powerful local unions in the country, Culinary Union Local 226 in Las Vegas, Nevada, operates in a right-to-work state and boasts close to 100% union membership. The union represents 55,000 hotel and airport food service workers in Nevada and has negotiated high wages and benefits for its members. Workers recognize the value provided by Culinary Local 226 and freely, and happily, pay the dues to fund those efforts.

As noted by Richard Yeselson, labor researcher, writer, and ardent union supporter:

“There is an argument sometimes made by union activists that unions should run persuasion campaigns to collect dues because the workers are more invested and supportive of an energized organization than when dues are passively/invisibly collected on a union’s behalf. There is some evidence that this is true.”

Yeselson credits Culinary Local 226’s “intense advocacy” for its exceptional success in a right-to-work state. As a result, executives for this union carry high credibility and influence, because there is no doubt they enjoy the firm support of their members.

The President of Oklahoma AFL-CIO said in 2012 that since his state adopted a right-to-work law in 2001, his union has not noticed any significant decrease in membership:

“Somebody asked me how many workers got out because of right-to-work and I said, well, we don’t track that number…It’s like any other workforce, where 10% cause you 90% of your problems. Those are the ones that bailed out of paying dues.”

Executives at these unions are not losing members because of their state’s right-to-work law; they are simply working harder to keep their members happy and satisfied. The Oklahoma AFL-CIO President says his union discovered after that state became right-to-work that “our labor-management relationship was terrible,” and those relationships have since improved.

And the extent to which union membership has declined in right-to-work states because of the right-to-work law is questionable when considering the long-term national decline over the same time periods. Nationally, the rate of union membership has steadily declined since 1983, dropping from 20.1% in 1983 to 11.3% in 2013, a decrease of 43.8% over the three-decade period.

Twelve states were right-to-work states within a year of passage of the

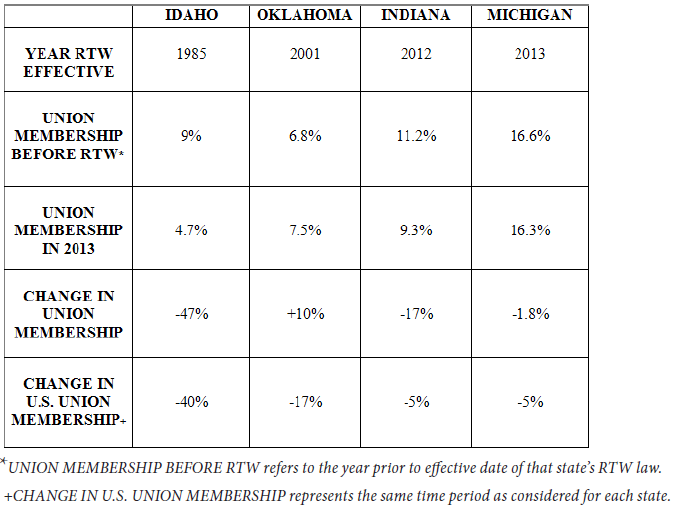

Taft-Hartley Act in 1947. Between 1951 and 1976 eight more states became right-to-work. So just four states have become right-to-work in recent decades; Idaho in 1985, Oklahoma in 2001, Indiana in 2012 and Michigan in 2013. The impact of right-to-work legislation on union membership is difficult to quantify for the first 20 right-to-work states, since the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) did not begin collecting data on union membership until 1983.

However, based on BLS data since then, the decline in union membership in the four most recent right-to-work states has not been nearly as precipitous as predicted by right-to-work opponents, when the general decline in national union membership is taken into account (see table).

Since Idaho became right-to-work in 1985, the number of workers represented in that state declined from 9% in 1984 to 4.7% in 2013. That is a decrease of 47%. During that same time period, the national rate of union membership dropped from 18.8% in 1984 to 11.2% in 2013, a decrease of 40%.

Oklahoma became right-to-work in 2001, and union membership in that state has actually increased by 10%, from 6.8% in 2000 to 7.5% in 2013. During that same time period, the national rate of union membership dropped from 13.5% to 11.2%, a 17% decrease.

Indiana became right-to-work in 2012, and union membership in that state decreased from 11.2% in 2011 to 9.3% in 2013, a decrease of 17%. During that same time period the national rate of union membership dropped from 11.8% to 11.2%, a decrease of 5%.

Michigan became right-to-work in 2013, and union membership in that state decreased from 16.6% in 2012 to 16.3% in 2013. That is a decrease of just 1.8%, compared to the national decrease of 5% over the same period.

While most right-to-work states have union membership rates lower than the national average (the average in right-to-work states is 6.6%), there are several outliers. Right-to-work states Alabama (10.7%), Iowa (10.1%), Michigan (16.3%), Indiana (9.3%), Kansas (7.5%), Nebraska (7.3%), Oklahoma (7.5%) and Nevada (14.6%) have relatively high unionization rates, while non-right-to-work states Colorado (7.6%) and New Mexico (6.2%) have low unionization rates.

Based on this data, it is clear that lower unionization rates in right-to-work states cannot be attributed solely to those states’ right-to-work laws.

Union membership has been declining nationally for three decades. But many right-to-work states have high unionization rates. Some experts theorize the typically lower union member rates in right-to-work states are due to those states’ historical dislike of unions, and passage of a right-to-work law simply reflects that preference.

As the president of the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute, whose mission is to “protect and improve the economic conditions of low and middle income workers,” notes, “There is a general, across the board decline in unionization in the U.S. I don’t know that the decline ... is greater in the original right-to-work states than it is in the non-right-to-work states.”

The Future of Right-to-Work

Labor unions have challenged the new right-to-work laws in Oklahoma, Indiana and Michigan. Those legal challenges, so far, have not been successful.

In November 2014, the Indiana Supreme Court unanimously upheld that state’s new right-to-work law. In Michigan, a state appeals court upheld the new law and a federal district court upheld the core components of the right-to-work law; it is now under consideration by that state’s supreme court. The Oklahoma Supreme Court rejected two attempts by labor unions to overturn that state’s right-to-work law in 2004.

Another case may lead to every state becoming “right-to-work” for some government employees. In July 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Illinois home health care workers cannot be forced to participate in a union or pay “agency fees” or dues. In Harris v. Quinn, the court ruled those workers are “partial public employees” and are not subject to a law that allows public sector unions to collect mandatory union dues, or agency fees, as a condition of employment.

Unlike regular government employees, home health care workers do not work for the state and are generally not paid directly by the state; they are care providers who work for the disabled or elderly in private homes and are paid from the government entitlement benefits received by their customers. Often these workers care for a family member and their union dues are automatically deducted from their loved-one’s monthly Medicaid check. In many non-right-to-work states, including Washington, home health care workers are required to pay union dues or agency fees, even if they do not want to be a union member.

The Harris ruling could impact hundreds of thousands of forcibly unionized home health care workers in California, Oregon, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Vermont, Washington and Connecticut. Already, Illinois has agreed that the ruling means state-subsidized home day care providers cannot be forced to pay union dues, known as “fair share fees.”

In Washington, the state has agreed to implement the decision in Harris pending the outcome of a lawsuit (Centeno v. Dept. of Social and Health Services) to determine whether the Harris decision applies to home health care workers in this state. Individual home care workers in Washington may now decline to join the union and pay union fees. However, if the court rules in Centeno that the Harris decision does not apply to the union in Washington state, the earlier union security contract clause and forced unionization of individual home care workers will be enforced.

Many legal scholars believe the ruling in Harris could lead to overturning a previous court decision that allows public sector workers to be forcibly unionized in non-right-to-work states. That case, Abood v. Detroit Board of Education, set the precedent in 1977 that allows government employees to be required to pay union dues or agency fees for representing them, even if they do not want that representation.

Writing for the majority in Harris, Justice Alito expressed his concern with Abood, saying:

“Agency-fee provisions unquestionably impose a heavy burden on the First Amendment interests of objecting employees.”

In another Supreme Court ruling in 2012, Knox v. SEIU, the justices expressed concern that Abood may not sufficiently protect the First Amendment freedom of association rights of workers forced to pay dues to an organization. The Court found the union’s “opt out” fee policies, which allow the union to charge fees to workers unless they opt out of the automatic paycheck deduction, “approach, if they do not cross, the limit of what the First Amendment can tolerate.”

Pro right-to-work groups are already signaling their intention to use the Knox and Harris decisions as the foundation for a lawsuit to overturn Abood. By most accounts, a ruling that reverses Abood and makes it illegal to require government workers to pay union dues or agency fees for services they may not want, would lead to the same rights for private sector workers. If the Supreme Court someday follows this reasoning and asserts the freedom of association of all workers, it would make every state a right-to-work state.

Conclusion

As private sector union membership continues to decline, public support for labor unions appears to be fading. The emergence of right-to-work legislation in several states is evidence that policymakers and voters are rethinking the role of labor unions in today’s modern workplace.

Unions were once an important means by which mistreated workers organized and demanded safe working conditions and fair wages, but unions have since evolved into something altogether different. Instead of advocating on behalf of workers, unions have increasingly turned into organizations that advocate for political causes that benefit union leadership more than union members. Union executives are heavily involved in securing political campaign donations, and over 90% of union giving goes to candidates of one party. Increasingly, private sector workers reject labor’s newly politicized role and resist the notion they should be forced to support that new role.

Right-to-work laws do not ban unions or prevent them from serving the interests of their members. Right-to-work laws do not force unions to represent non-paying “free riders” who take advantage of a union’s representation but do not pay their share. Rather, right-to-work laws require unions to give workers a choice about financially supporting those efforts.

When unions are focusing their efforts on representing and servicing members, there is less time and there are fewer resources to engage in the political activities that so many union members find objectionable. This redirection of union efforts results in a business climate that is more attractive to new and existing businesses.

Right-to-work states boast better growth, wages and employment than non-right-to-work states.

Twenty-four states have decided right-to-work is right for their workers. Based on the overwhelming research of right-to-work states, right-to-work has been right for those states’ workers, employers and economy. The question now is right-to-work right for Washington?