So-called “green buildings” using the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) system are a key component of government strategies to reduce CO2 emissions in Washington state. A new study looks at how effective those buildings are at reducing emissions.

How do they perform? The simple answer is extremely poorly. The total annual CO2 reductions for the 23 million square feet in the 50 LEED-certified buildings in Seattle could be matched for less than $1,000 per building per year.

This is another dramatic example of why Washington state spends a great deal of time and money on the topic of climate change but fails to meet every CO2 target.

Buildings that meet the LEED standard are a key component of government strategies to reduce CO2 emissions. The 2018 Seattle Climate Action plan notes that new city-owned buildings must achieve LEED Gold certification. King County government buildings “are required to strive for LEED Platinum certification.” The purported justification for these rules is to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from buildings to meet CO2-reduction targets. The new research demonstrates, however, that LEED-certified buildings yield tiny environmental benefits. Additionally, it shows that LEED-certified buildings perform more poorly in Seattle than most other U.S. cities.

The new study from researchers at Oberlin College, “Energy and Greenhouse Gas Savings for LEED-Certified U.S. Office Buildings” uses new data from thousands of buildings in ten U.S. cities to compare the energy use of buildings certified by the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) to buildings not certified using that system. The results show how poorly LEED-certified buildings perform.

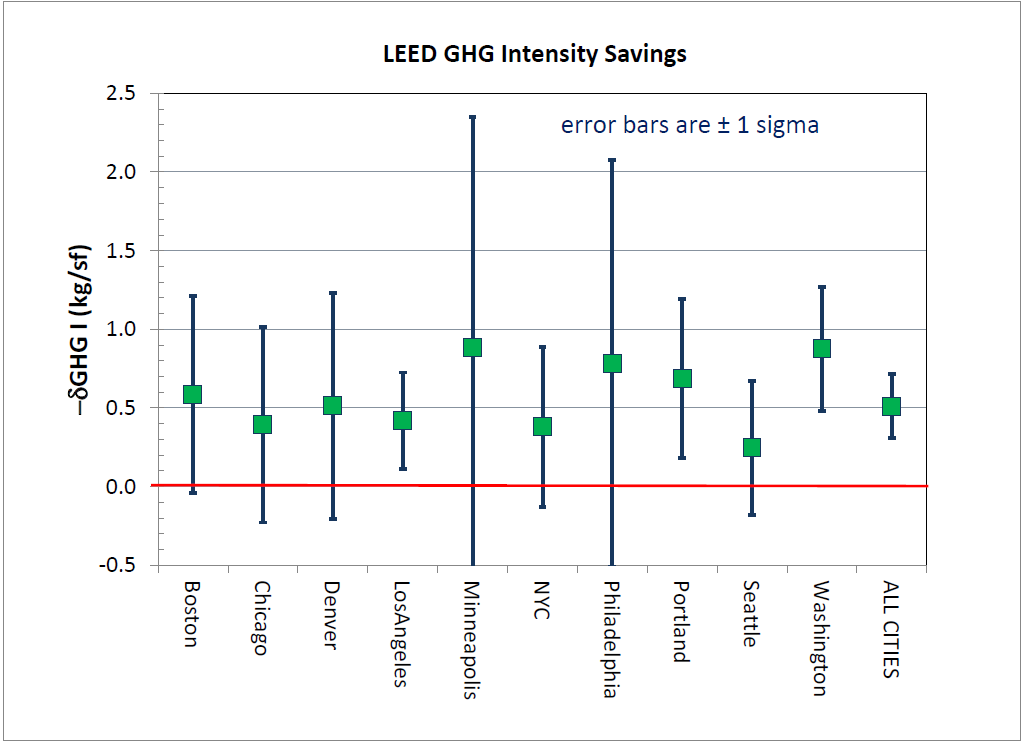

The study used data from 459 buildings in Seattle, 50 of which were LEED-certified. The analysis showed that LEED-certified buildings produced only 5 percent fewer greenhouse gases than uncertified buildings. This is an extremely small amount and far below standard promises that LEED-certified buildings reduce emissions by about 25-30 percent. Nationally, the average reduction in GHG emissions from LEED-certified buildings in the study was about 7 percent.

The study used data from 459 buildings in Seattle, 50 of which were LEED-certified. The analysis showed that LEED-certified buildings produced only 5 percent fewer greenhouse gases than uncertified buildings. This is an extremely small amount and far below standard promises that LEED-certified buildings reduce emissions by about 25-30 percent. Nationally, the average reduction in GHG emissions from LEED-certified buildings in the study was about 7 percent.

To put this in context, I calculated the value of the CO2 emissions avoided by LEED-certified buildings in Seattle. The study examined 50 LEED-certified buildings with a total are of 2.2 million square meters (about 23 million square feet). The study found the LEED-certified buildings in Seattle reduced CO2 emissions by an average of 2.6 kilograms per square meter every year. Across all 50 buildings, that amounts to 5,720 metric tons of avoided CO2 emissions. Is that a lot? No.

Seattle City Light pays about $7 to reduce one metric ton of CO2 by investing in projects that reduce methane emissions. Using that metric, the combined CO2 reduction for all 50 LEED-certified buildings included in the study is worth $40,040 a year. Simply filling out the paperwork to receive LEED certification can cost that much.

These buildings cost millions of dollars to build, and LEED certification adds significant cost. Using Seattle City Light’s approach, building owners could pay $1,000 a year and yield greater CO2 reduction than building to LEED standards.

The USGBC seems to know this is the case. As the study notes, “The USGBC recognized the need for energy performance data and, beginning with version 2009, required all LEED-certified buildings to provide annual energy data for the first five years of operation. Still, a decade and thousands of certifications later, the USGBC has neither made these data public nor published any scientific analysis of these data.” The fact that they refuse to release energy data says a great deal about how poor the data probably are.

Advocates of LEED point to building models that show the buildings save energy. The Oberlin study also examined that, comparing modeled projections for the buildings with actual results. Across all 4,168 buildings included in the study, researchers found “the measured savings fall well below the expected savings. The total measured source energy savings for these offices is just 19% of the total predicted source energy savings.”

These results are consistent with my research on “green” school buildings in several states. The buildings consistently performed poorly, sometimes worse than traditionally built schools which cost less. Despite that reality, school districts continue to spend more for LEED-certified construction because, as one school district’s facilities director explained, the school board members want a plaque that says “green-certified” they can hang on the school.

It is just one more example of how, despite the rhetoric of a “climate crisis,” politicians and government staff prioritize image over environmental effectiveness.