It is rare that we have good news about salmon runs in Washington state, so it is worth highlighting that for the first time in many years, coho are being caught on the Elwha River.

After the dams were removed a decade ago, fishing has been halted to allow salmon populations to recover. Now that the moratorium on coho fishing has been lifted for a limited catch, comments from tribal members show how important it is that coho returns have increased. It is something to celebrate.

The story is not as good for Chinook, which are still struggling on the Elwha. The contrast between the two species, and how poor Chinook numbers are being portrayed to fit an ideological narrative, is a lesson in the scientific and political challenges we face when trying to improve salmon runs.

In the Seattle Times, Lynda Mapes, a long time opponent of the Snake River dams, writes about members of the Lower Elwha Klallam tribe catching coho for the first time in many years. Removing the two dams on the Elwha opened up new habitat which is likely contributing to the improved returns. In a similar way, Washington state has been removing fish blockages on roads to open up habitat for coho and other species. Functionally, removing the Elwha dams is like removing two large fish blockages.

Chinook haven’t been as responsive to these kinds of removals, however. The original Elwha plan anticipated harvesting Chinook five years after the removal the dams, but the moratorium has been extended and populations are still struggling.

Despite that, Mapes claims that while Chinook returns were “modest,” the 2022 returns were “twice the pre-dam removal average.” The admission that the returns are modest is a significant change of tune from three years ago when she claimed Chinook were “surging back.” After two good years, returns have been relatively low for the past three years. In fact, the 2022 Chinook returns were actually smaller than between 2013 and 15, just after dams were removed and thn potential benefits of dam removal were not meaningful.

The source of Mapes’ claim that 2022 returns are twice the pre-dam average is unclear. The only data she provides in the story is from 2009 forward.

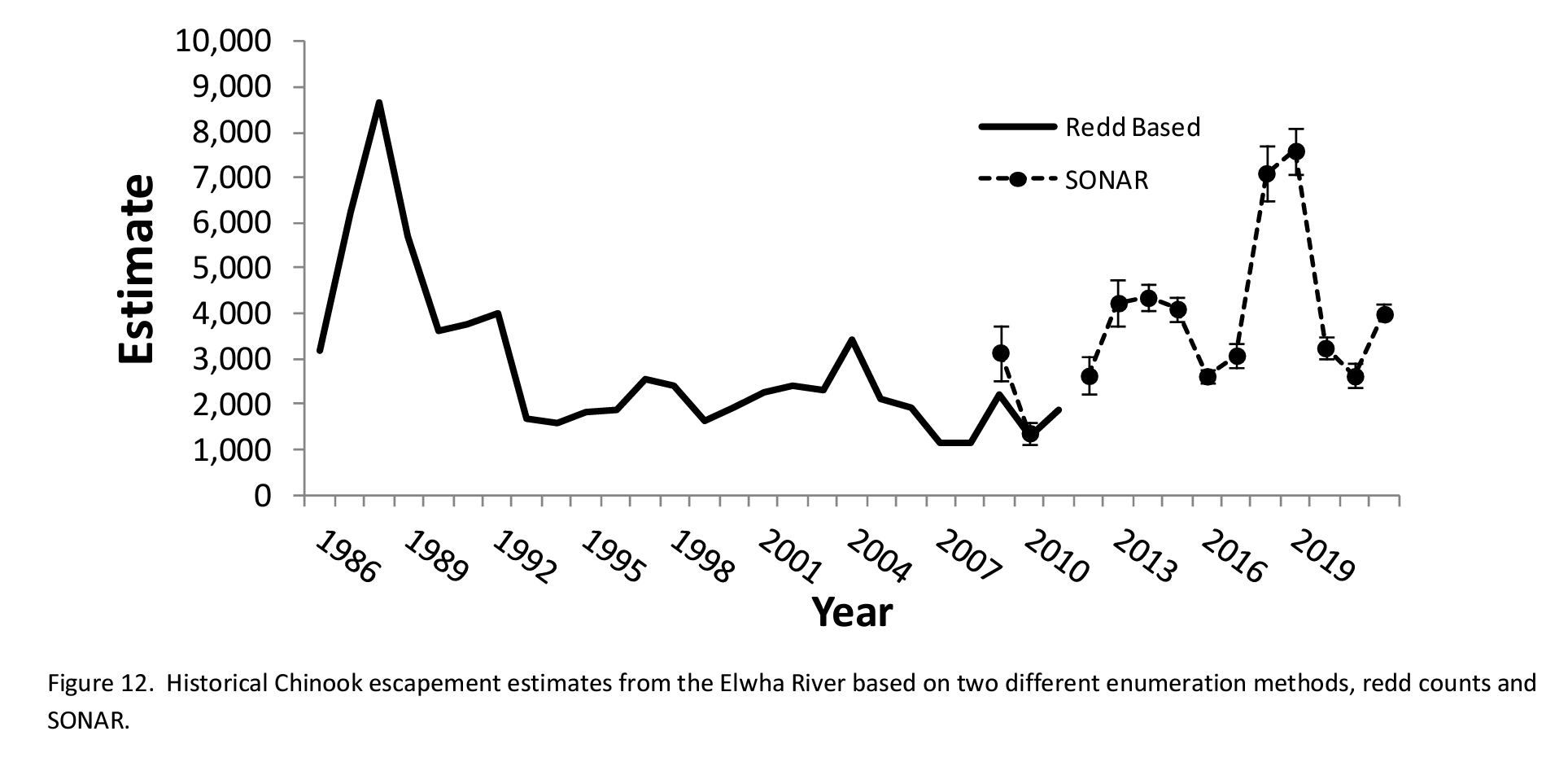

The estimate likely comes from the “2022 Elwha River Chinook Escapement Estimate Based on DIDSON/ARIS” report to the Olympic National Park and the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe. The data for one of the charts Mapes includes in her story likely comes from Table 3 of that report. For returns prior to 2009, the report includes this chart estimating Chinook populations since 1985. Based on a cursory look, Mapes’ claim about the population growth appears to be accurate, although Chinook returns in recent years are similar to those in the late 1980s.

The estimate likely comes from the “2022 Elwha River Chinook Escapement Estimate Based on DIDSON/ARIS” report to the Olympic National Park and the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe. The data for one of the charts Mapes includes in her story likely comes from Table 3 of that report. For returns prior to 2009, the report includes this chart estimating Chinook populations since 1985. Based on a cursory look, Mapes’ claim about the population growth appears to be accurate, although Chinook returns in recent years are similar to those in the late 1980s.

The report, however, specifically notes that counts prior to 2009 should not be compared to those after 2009 because the method of estimating Chinook population changed significantly.

As the graphic notes, prior to 2009, Chinook population estimates were based on a count of redds, which is a depression in the bottom of a stream where salmon lay their eggs. The estimated population was generated by counting redds and multiplying by 2.5 and adding the number of salmon removed for hatchery production.

Since 2009, counts have been generated using sonar. This is more accurate and also results in a higher count. As a result, comparing sonar counts to estimates based on redds is not appropriate.

The 2022 report makes this point. The authors write, “We compared our escapement estimate of 3,998 Chinook with other data collected in the watershed.” The estimate based on a count of redds plus adult Chinook removed above sonar sites resulted in an estimate of 2,400 fish, about 78% of the sonar count. The authors wrote, “Our SONAR based estimate being greater than the redd count plus broodstock removal total is consistent with previous years and not unexpected for a variety of reasons, mainly undetected spawning and redd superimposition.” Put simply, researchers know that comparing fish counts after 2009 to those before has significant problems.

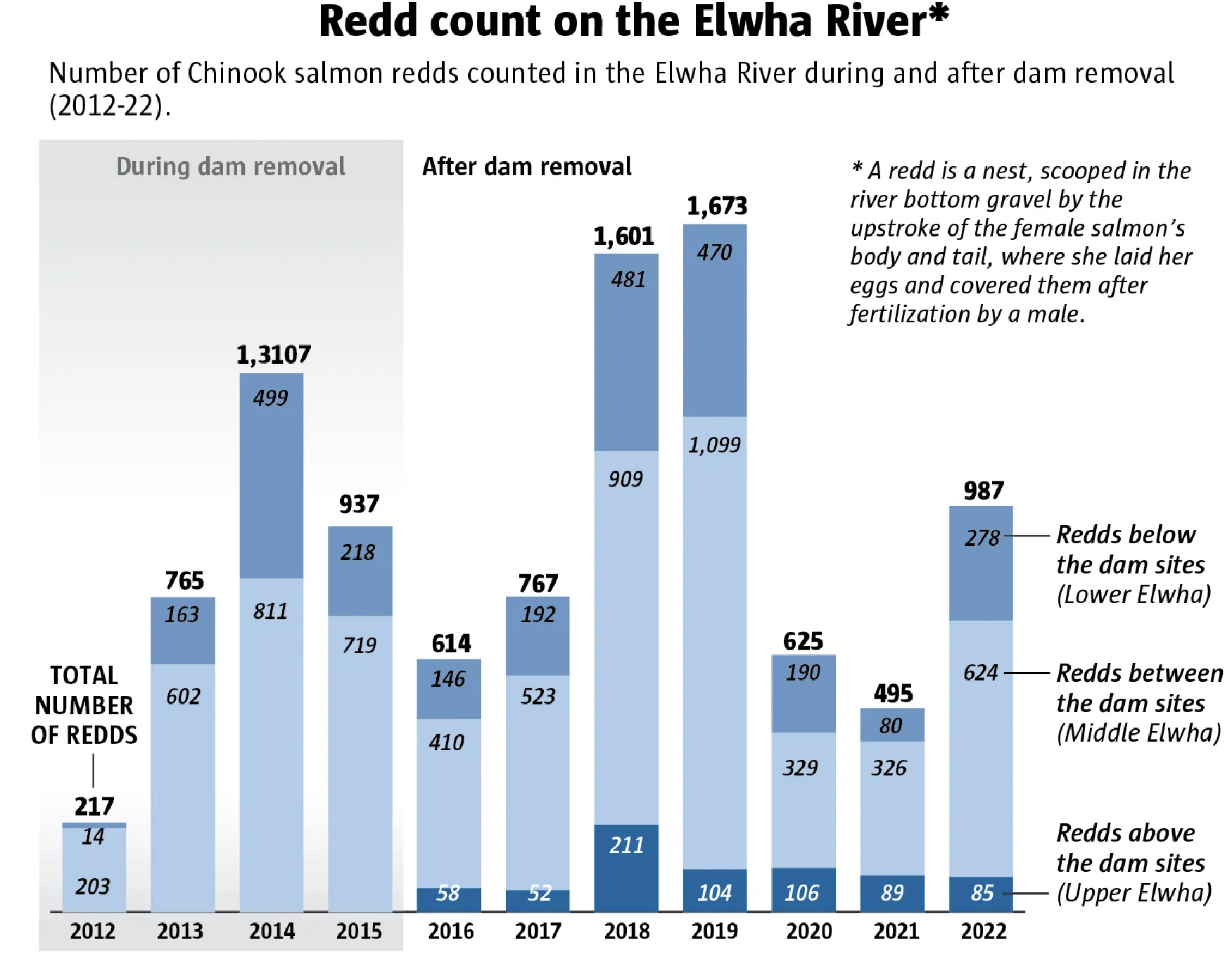

It may be that Chinook populations have slightly increased since the dams were removed, but the increase is likely smaller than Mapes implies. The data she does provide about the number of redds counted since 2012 indicates the size of the margin of error.

It may be that Chinook populations have slightly increased since the dams were removed, but the increase is likely smaller than Mapes implies. The data she does provide about the number of redds counted since 2012 indicates the size of the margin of error.

The article provides this graphic listing the annual number of Chinook redds counted on the Elwha River and their location. Using the pre-sonar method demonstrates how different the counts are.

Using the estimation methodology based on the number of redds – multiplying by 2.5 and then adding a percentage of fish removed by WDFW – we can compare population estimates from sonar since 2012. There are some significant differences.

Assuming the percentage of Chinook removed by WDFW is relatively similar, since 2013 the redd-count estimations would range between 63 and 93 percent of the sonar count. That is a wide range of uncertainty.

Using the redd-count approach, Chinook returns in the decade before the dams were removed ranged from about 2,000 to 3,000 fish. Adjusting for the undercount based on sonar and redd counts during the past decade, the actual Chinook populations in the Elwha range from about 2,100 up to 4,750. This would put the 3,998 counted in 2022 above average for the decade prior to dam removal, but not double the average. With the exception of two good years, Chinook returns on the Elwha have ranged between 2,628 and 4,360, very similar to the period before dam removal.

This is an estimate and we have requested some data not included in the report that would allow a more precise comparison. We will update the information when we receive it.

The hope is that the good years of 2018 and 2019 become the norm in the near future. We may get a good idea this year of whether those increases are sustainable since Chinook from the 2018 run are returning this year. The fact that the Chinook fishery is closed is a good indication that scientists on the ground are still concerned.

Removing the Elwha dams may ultimately be successful at increasing Chinook populations on the Elwha to the point where the tribe can again harvest fish and we will see the same happy comments from tribal members again in the future.

We are not there yet and the impact of dam removal is being intentionally exaggerated by some for political reasons. The Biden Administration even cited returns on the Elwha as a justification to remove the Snake River dams. Such claims are really indefensible given the fact that the Snake River dams are completely different than the Elwha dams. Exaggerating success on the Elwha is a way for some, like Mapes, to argue that destroying the Snake River dams will also increase salmon populations.

It is another example of the desire of some to move away from sustainable, science-based approaches to salmon recovery and look for sliver bullets that fit their ideology. That mindset routinely dismisses real-world data and the important caveats and details of scientific evidence.

We can celebrate the success of increases in the coho population on the Elwha and still be honest about the challenges that are faced by Chinook and the limitations of dam removal in helping them recover.