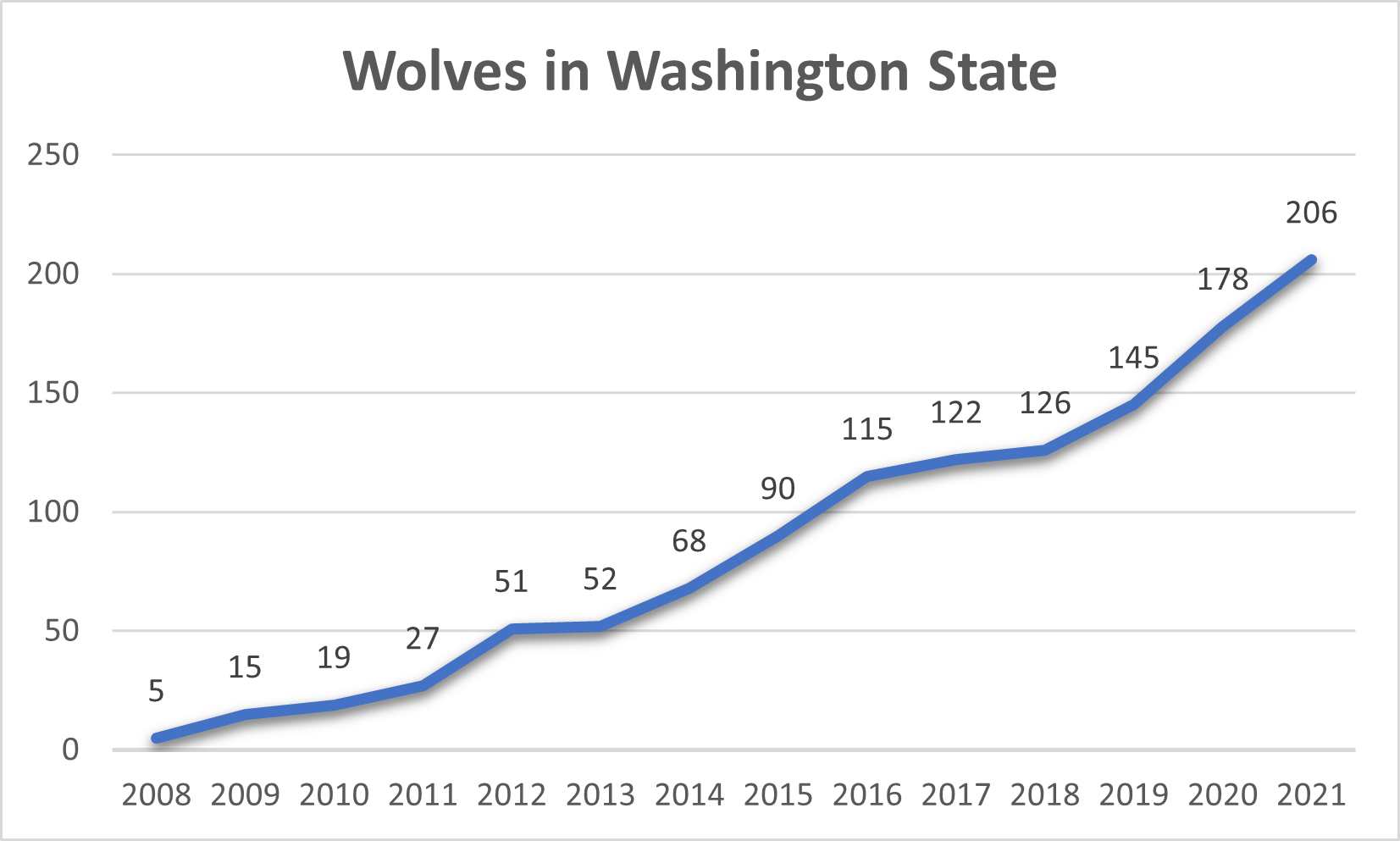

Washington’s wolf population saw another significant increase, growing by 16 percent in 2021 according to the Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW). The number of packs grew to 33 from 29 in 2020, and the number of breeding pairs increased from 16 to 19.

The consistent growth of the wolf population is good news and is the result of hard work of WDFW staff, the Wolf Advisory Group, and the ranchers in NE Washington who have taken steps to reduce wolf attacks.

These good numbers contradict the rhetoric from some environmental groups and the governor about wolf populations. In response to a 2020 letter from the Center for Biological Diversity which claimed, “wolf management has been a sordid affair.” The governor said he accepted the letter (despite the data showing rapidly growing populations) and has pushed for tougher restrictions on ranchers in Northeast Washington.

These good numbers contradict the rhetoric from some environmental groups and the governor about wolf populations. In response to a 2020 letter from the Center for Biological Diversity which claimed, “wolf management has been a sordid affair.” The governor said he accepted the letter (despite the data showing rapidly growing populations) and has pushed for tougher restrictions on ranchers in Northeast Washington.

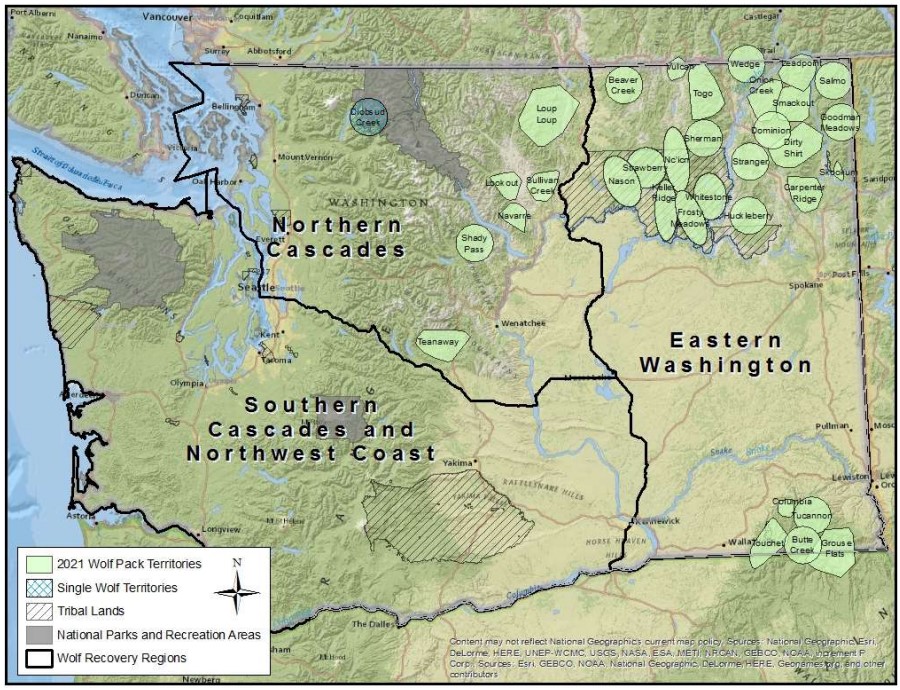

This is remarkable when considering the status of the wolf population. Both the U.S. government and the Colville Confederated Tribes consider wolves recovered in Eastern Washington.

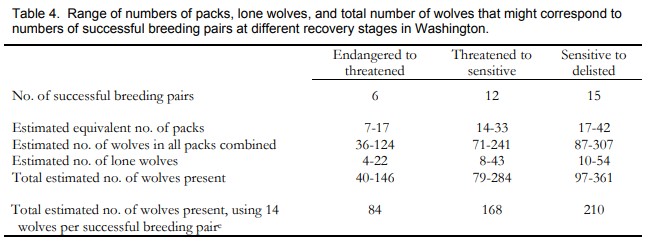

Additionally, the wolf population in the Eastern Washington region exceeds the standards set by the state to be considered recovered. The state says it can begin the process of delisting wolves if there are 15 breeding pairs for three consecutive years, with at least four pairs in each of the three regions. Washington has now had four years with 15 or more breeding pairs. The  state's Wolf Management and Conservation Plan estimated that delisting would require 15 breeding pairs, between 17 and 42 packs, and about 210 wolves. That is almost precisely where the state's wolf population is today.

state's Wolf Management and Conservation Plan estimated that delisting would require 15 breeding pairs, between 17 and 42 packs, and about 210 wolves. That is almost precisely where the state's wolf population is today.

Most of those wolves, however, are in one corner of the state, taking advantage of the favorable habitat. While the population estimates were fairly accurate, the projection that packs would disperse across the state turned out to be inaccurate. That concentration of wolves in one area means that the state isn’t considering delisting and that ranchers there bear a  disproportionate burden of depredations and the cost to prevent wolf attacks.

disproportionate burden of depredations and the cost to prevent wolf attacks.

The delisting criteria are based on the false assumption that wolves would spread out across the state as their population increased. Now that this assumption has been proven incorrect, it is time to reconsider the state’s metrics and follow the lead of federal and tribal governments and use the Eastern Washington region as a model for delisting wolves in the rest of the state when population targets are achieved. Beginning a regional delisting process would acknowledge the tremendous progress that has been made, the work of ranchers and others to reduce conflict, and the costs a small group of people are paying so we can all enjoy the recovery of a magnificent animal.