Disclosure filings show major donors would have profited from Prop. 1 spending

On April 22nd, the people of King County voted on Proposition 1, a ballot measure to increase regressive sales and car tab taxes to prevent a plan proposed by County Executive Dow Constantine from cutting community bus services by 16% (down from his planned 17% cut after Metro reported windfall revenues of $32 million). To the dismay of many in the King County establishment, the measure failed by a wide margin.

The campaign finance filings for the pro and anti campaigns are now available. A review shows that many of the major donors to the pro Proposition 1 campaign, especially unions, would have directly profited from its increases in public spending. Here’s what the numbers show:

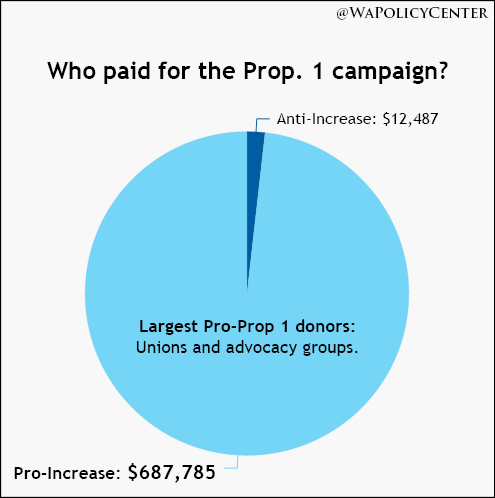

Finding 1: The pro campaign outspent the anti side by 55 to one.

The most striking finding of the disclosure reports is that the pro campaign massively outspent the anti campaign. The anti campaign spent $12,487. The pro campaign spent $687,785, outspending their opponents by a margin of 55 to one.

The finding is a blow to those pushing for government-funded campaign financing. Advocates of giving tax money to political candidates base their proposal on the assumption that private campaign giving corrupts the election process. The vote on Proposition 1 shows that the side that spends more money, even by large amounts, does not always prevail.

Finding 2: The largest pro campaign donors, mainly public-sector unions, would have profited from Proposition 1 spending.

Many of the pro side’s donations came from entities and businesses that would have directly profited from Proposition 1’s increase in public spending.

The largest single donor to the pro side was AFSCME-WFSE Local 1488, which gave $50,000. The second-largest donor was the Transportation Choices Coalition, an advocacy group that lists King Country Metro, Sound Transit and City of Seattle among its partners and funders.

The third largest donor to the pro side was the Amalgamated Transit Union, which represents Metro bus drivers.

In December, the Amalgamated Transit Union rejected a pay-increase contract offered by Metro managers, arguing the County should give its members more money. Proposition 1’s regressive tax increases would have authorized County leaders to collect $130 million more per year from people living in King County. That revenue would have allowed County officials, in renewed contract talks, to give executives at the Amalgamated Transit Union all or nearly all of the increased money they are seeking.

Finding 3: Nearly one-fifth of Proposition 1 campaign money came from mandatory dues.

In Washington state, unions receive money from mandatory dues taken from worker paychecks and transferred each month into union bank accounts. When union executives make pledges to political campaigns, the money they give is taken from worker paychecks.

Workers in Washington state are not protected by a Right to Work law, which in other states gives workers the right not to join a union and still keep their jobs. For many public-sector workers, union membership is mandatory, and the money transferred each month to the union comes from public payroll budgets.

In the case of Proposition 1, public money was deducted from worker paychecks and given to a political campaign to support passage of a ballot measure to increase regressive taxes. Money from the new taxes would have gone to fund a bus drivers’ contract that would have increased Metro’s public payroll. Amalgamated Transit Union dues are deducted from the same payroll. Passage of Proposition 1 would have increased the amount of public money, through mandatory dues, transferred each month to the bank accounts of the Amalgamated Transit Union.

Finding 4: Nearly one-fifth of Proposition 1 campaign money came from just 11 unions.

Nearly one-fifth of all pro Proposition 1 campaign donations, a total of $135,000, came from just eleven unions. Examples of the largest donors include Amalgamated Transit Union Local 587 ($20,000), and Laborers Local 242, Laborers Local 440, Aerospace Machinists #751, SEIU 1199 NW and SEIU 775 NW, which gave $5,000 each.

These 11 Union alone outspent their anti Proposition 1 opponents by more than 10 to one.

Workers were not asked individually whether they thought part of their wages should go to pay for the Proposition 1 campaign. Many union members likely found themselves in the odd position of voting against Proposition 1, so their sales tax and car fee costs would not go up, while executives at their own union used money from paycheck deductions to promote the opposite cause.

Conclusion: Full disclosure of political spending in the Proposition 1 campaign was not available until after the election, so the public was not aware of whether and to what extent donors on the pro side, especially unions, stood to profit from the increases in regressive taxation under the measure they were advocating.

Seattle Mayor Ed Murray has announced his own plan to increase regressive taxation in the city, and another political campaign may soon be under way. It will be important for the public to be informed, to the extent possible, of the relationship between campaign donors and who will benefit from higher public spending under Mayor Murray’s plan.